Updated 12/31/14 to addressed the alleged connection between Mary Hyanno and Canonicus

In this post I will review our family lineage back to Sgt William Cornell of Roxbury MA, Hartford CT and Middletown CT. I will use the spelling “Cornell” throughout. Early records show he signed his name “Cornell” and during most of his life, but later records and generations shifted the spelling to “Cornwell” and then “Cornwall”. I tend to prefer the spelling used by the individual when doing these posts. I have over time switched between all three spellings, so you will see remnants of them in images and file names. But for the purpose of this post, I will stick with the original “Cornell”.

I begin with the lineage from myself back to William Cornell:

I have not seen any issue or ambiguity with this lineage, so I will not dwell on it anymore except to bring in other branches of import when needed. So let’s review not just the life of William Cornell, but the world he lived in based on documented evidence.

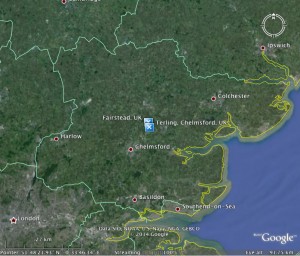

According to “The Great Migration: Immigrants to New England, 1634-1635“, by Robert Charles Anderson in 1996-2001, William Cornell was born in 1609 in Fairfield [should be “Fairstead”], Essex, England.

According to Family Research records (England, Births and Christenings, 1538-1975) he was born in Terling, Essex, England on 25th May 1609.

His father was William Cornell (1562-1625) of Terling, Essex, England and his mother was Jone Martyne (1570-1616).

Terling and Fairstead are located right next to each other in Essex County, north of London, so I do not believe these records are in any real conflict. See map below [click to enlarge all images]:

As I investigated side branches of my family in New England I discovered many in my family tree – and many outside the tree who played a key role in the region during William Cornell’s life – hailed from Essex, England. We will come back to this nexus at Essex, England many times. It is one aspect of my family that made it highly likely there was more than a passing interaction with the Indians of New England. Because those colonists from Essex tend to have held a unique view on how to interact with the Native Americans of New England.

We next find William and his first wife Joan (Ranke) coming to America in 1633 and arriving in Roxbury MA, not far from the Boston settlement. [According to “The Great Migration: Immigrants to New England, 1634-1635“, by Robert Charles Anderson in 1996-2001]. See map below for location of Roxbury.

- 1630: September 28, The first Puritan settlers arrive in Roxbury, led by William Pynchon (1589-1661), three weeks after the founding of Boston. The town is originally called “Rocksberry.” The town is named after the unique rock outcroppings later called Roxbury puddinstone. All the other Roxburys in the United States have their origin in Roxbury, Massachusetts.

- 1632: The first meetinghouse and burial ground are constructed [editor: in what will later be called John Eliot Square]. At this time, Washington, Roxbury, and Warren Streets and Dudley Square are laid out.

- 1635: Reverend John Eliot (1604-1691) founds the Roxbury Latin School [editor: that later moves to West Roxbury in 1922]. The school is the first preparatory school in the United States. Eliot is known as ‘The Apostle of the Indians’ for his efforts to christianize the Native Americans.

[Editor notes our my adjustments to make the text more clear]. The name William Pynchon will surface again later in this post.

Interestingly, our next record for William & Joane “Cornewell” is as members of John Eliott’s Church in Roxbury (per the William Cornell biography “William Cornwall and His Descendants“, by Edward Everett Cornwall, 1901):

The first record which we have of him is found in the Reverend John Eliot’s list of the members of his church in Roxbury, Massachusetts, which includes the names of :

” William Cornewell,

” Joane Cornewell, the wife of William Cornewell.”

The date 1633 is given just before and just after the entry of these names.

Here I must digress quite a bit to emphasize the importance of this record. As I noted in Part 1 of this series, John Eliott was renowned for his ministering to the natives and converting them to Christianity. He was the person who created an English version of the Massachusett/Algonquin language and had the first Bible printed in America in that language. John Eliott was the “Teacher” at Roxbury Church, and his life’s work is amazing, as was is relationship with Native Americans:

An important part of Eliot’s ministry focused on the conversion of Massachusett Indians. Accordingly, Eliot translated the Bible into the Massachusett language and published it in 1663 as Mamusse Wunneetupanatamwe Up-Biblum God.[6] In 1666, he published “The Indian Grammar Begun”, again concerning the Massachusett language. As a missionary, Eliot strove to consolidate Native Americans in planned towns, thereby encouraging them to recreate a Christian society. At one point, there were 14 towns of so-called “Praying Indians”, the best documented being at Natick, Massachusetts. Other praying Indian towns included: Littleton (Nashoba), Lowell (Wamesit, initially incorporated as part of Chelmsford), Grafton (Hassanamessit), Marlborough (Okommakamesit), a portion of Hopkinton that is now in the Town of Ashland (Makunkokoag), Canton (Punkapoag), and Mendon-Uxbridge (Wacentug). In 1662, Eliot witnessed the signing of the deed for Mendon with Nipmuck Indians for “Squinshepauk Plantation”. Eliot’s better intentions can be seen in his involvement in the legal case, The Town of Dedham v. The Indians of Natick, which concerned a boundary dispute. Besides answering Dedham’s complaint point by point, Eliot stated that the colony’s purpose was to benefit the native people.[7] Praying Indian towns were also established by other missionaries, including the Presbyterian Samson Occom, himself of Mohegan descent.

The Praying Town of Nashobah will show up again in another branch of my family that marries into the Cornell line. It is interesting this village is also near Chelmsford – so named I assume for the capitol of Essex, England.

While most of the pilgrims/puritans of New England were in fear of the Indians, a small band of historic figures (e.g., John Eliott, Roger Williams, etc) were more inclined to learn how to live with the natives than attack them. This group of “misfits” – for lack of a better word – show up in William Cornell’s life (and my family tree) over and over again.

And it all begins with Cornell’s membership in one of the more amazing Churches in New England, if not America: the Church of Roxbury, circa 1630’s.

Another prominent member of this church was Reverend Thomas Weld, also of Terling, Essex:

Thomas Weld (bap. 1595, d. 1661[1]), who came to Boston on 5 June 1632 on the “William and Francis”, was a Puritan emigrant from England and the first minister of the First Church in Roxbury, Massachusetts from 1632 to 1641.

…

After moving to New England in 1632 he became a strong opponent of John Wheelwright in the Antinomian debate and authored a book on the topic.[3] Weld also assisted in the composition of the Bay Psalm Book and became an overseer of the newly founded Harvard College. He was also an inquisitor at the trials of Anne Hutchinson during the Antinomian Controversy, and was one of her most vocal opponents.[4]

In 1641, he left most of his family in Massachusetts Bay Colony and returned to England on business for the General Court of Massachusetts. Among his instructions were the acquisition of an extension to the colonial charter to include the territory of present-day Rhode Island. This territory had been settled by Roger Williams and Anne Hutchinson, to the dismay of the Puritan leaders of Massachusetts. Weld created a fraudulent document (known as the “Narragansett Patent”) to bolster the Massachusetts claim to the territory.

Another notable member of the church at Roxbury plays a different role in the matters of Roger Williams and Anne Hutchison. He is John Coggeshall:

John Coggeshall (1601 – 27 November 1647) was one of the founders of Rhode Island and the first President of all four towns in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Coming from Essex, England as a successful merchant in the silk trade, Coggeshall arrived in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1632 and quickly assumed a number of roles in the colonial government. In the mid-1630s he became a supporter of the dissident ministers John Wheelwright and Anne Hutchinson. When Hutchinson was tried as a heretic in 1637, Coggeshall was one of three deputies who voted for her acquittal. Hutchinson was banished from the colony in 1638, and the three deputies who voted for her acquittal were also compelled to depart.

The story of Roger Williams and John Coggeshall would fill volumes. But here are a few snippets of their relationship with the Indians and European Settlers worth covering:

Roger Williams (c. 1603 – between January and March 1683) was an English Protestant theologian who was an early proponent of religious freedom and the separation of church and state. In 1636, he began the colony of Providence Plantation, which provided a refuge for religious minorities.

…Williams also married Mary Barnard (1609–76) on December 15, 1629, at the Church of High Laver, Essex, England.

…These three principles became central to Williams’ subsequent career: separatism, freedom of religion, and separation of church and state.

…Williams intended to become a missionary to the Native Americans and set out to learn their language. He also studied their customs, religion, family life and other aspects of their world. Williams came to see their point of view and developed a deep appreciation of them as people, which later caused him to question the colony’s legal basis for acquiring land, and thus led to controversy and his eventual exile.

…In the spring of 1636, Williams and a number of his followers from Salem began a new settlement on land that Williams had bought from Massasoit [editor: of the Wampanoag Tribe], but Plymouth authorities asserted that he was still within their land grant and warned that they might be forced to extradite him to Massachusetts. They urged Williams to cross the Seekonk River, as that territory lay beyond any charter. The outcasts rowed over to Narragansett territory, and bought land from Canonicus and Miantonomi, chief sachems of the Narragansetts.

As can be seen, Roger Williams had a very non-Puritan, non-colonial perspective on life. As did John Eliott and John Coggeshall.

The settlers of Rhode Island will come into Cornell’s life a bit later during the Pequot war. But note here the schism developing between the mainstream colonists and this band of separatists. Anne Hutchinson plays a very unique role in the schism, the role of an open minded and vocal woman:

Anne Hutchinson, born Anne Marbury (1591–1643), was a Puritan spiritual adviser, mother of 15, and important participant in the Antinomian Controversy that shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. Her strong religious convictions were at odds with the established Puritan clergy in the Boston area, and her popularity and charisma helped create a theological schism that threatened to destroy the Puritans’ religious experiment in New England. She was eventually tried and convicted, then banished from the colony with many of her supporters.

…She lived in London as a young adult, and married there an old friend from home, William Hutchinson. The couple moved back to Alford, where they began following the dynamic preacher named John Cotton in the nearby major port of Boston, Lincolnshire. After Cotton was compelled to emigrate in 1633, the Hutchinsons followed a year later with their 11 children, and soon became well established in the growing settlement of Boston in New England.

…As a follower of Cotton, she espoused a “covenant of grace,” while accusing all of the local ministers (except for Cotton and her husband’s brother-in-law, John Wheelwright) of preaching a “covenant of works.” Following complaints of many ministers about the opinions coming from Hutchinson and her allies, the situation erupted into what is commonly called the Antinomian Controversy, resulting in her 1637 trial, conviction, and banishment from the colony.

…With encouragement from Providence founder Roger Williams, Hutchinson and many of her supporters established the settlement of Portsmouth in what became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations.

We shall see another ancestor of mine – one Tryall Shepard – demonstrate a similar tendency to be an outspoken (and respected) woman of early New England.

It is not clear exactly how long the Cornell’s were in Roxbury being buffeted by these social forces. But they were there, up close to major players. There is no indication of angst or concern, in fact the record appears to show William Cornell becoming a defender of Roxbury in more ways than one.

We have strong evidence William Cornell became a Sergeant in the Roxbury militia. We know he fought in the Pequot War (1636-1637) , and according to this site covering the war he was a member of Captain John Underhill’s Bay Colony forces:

Sergeant William Cornwell

(d. February 21, 1678, Middletown, Connecticut Colony) Of Roxbury, Massachusetts Bay Colony. Served in the Pequot War under Captain John Underhill.

The Pequot War also can consume volumes of writing, but the important essence of the war as it relates to one William Cornell is the fact he participated under the command of another one of New England’s famous misfits: Captain John Underhill. A little retrospective is in order to once again establish a framework of time and geography – especially when it comes to the Massachusetts Bay Colony Militia:

- On 4 March 1628/9 the Bay Colony received its charter, which included total control over internal military and political organization. The governing body (then still located in England) issued its “First General Letter” of instructions on 17 April of that same year (ref. Records Mass. 1:37i-39, 386-398) to CPT John Endecott appointing him governor” of the “plantation” at Naumkeag (Salem) and directing him to undertake the military organization of the trading post and settlement, which had been established the previous year.

- Endecott had travelled to Salem in 1628. At his request weapons and uniforms for 100 men were shipped over in 1629 to outfit a company organization which corresponded to contemporary European norms and included 1 captain, 1 lieutenant, 1 ensign, 3 sergeants, 3 drummers, possibly 1 corporal, and 90 or 91 privates.

Note the militia structure in this period limited the Sergeants to 3 in total per company of soldiers. Captain Underhill had one company, thus only three Sergeants:

The companies in the Bay proper, covering the 1630 settlements, are all ruled to have an organization date of 12 April 1631, based on the law requiring training passed by the General Court. These companies were:

- Captain John Underhill’s (Boston and Roxbury);

- Daniel Patrick’s (Watertown, Medford and Newtown);

- Richard Southcot’s (Dorchester); and

- John Endecott’s (Salem).

Some other points of context:

- Two military veterans from Europe were hired to train the colony’s militia: Captains Daniel Patrick and John Underhill (ref. Records Mass. 1:99, 103).

- Note that initially some companies were split between several towns (ref. Records Mass. 1:127), that captains appointed their non-commissioned officers (ref. Records Ma. 1:109), and that by 1635/6 each company had its own colors which were carried by the ensign (ref. Records Mass. 1:169).

- Significant “firsts” include the 26 July 1631 initial commissioning of junior officers by the General Court (ref. Records Mass. 1:90); the first reference to split training (which included reference to the fact that drill started at 1300 hours) by Captain John Underhill’s company which was spread between Boston, Roxbury, Charlestown, Mystick, and New Town (ref. Records Mass. 1:90)

So we have clear evidence Underhill commanded the members of the Militia living in Roxbury in 1631 – where William Cornell arrives one or two years later and clearly joins and is given one of three precious Sergeant slots.

Captain John Underhill commanded his company in many excursions (Transgressing the Bounds : Subversive Enterprises among the Puritan Elite in Massachusetts, 1630-1692), many of which it would seem Sgt William Cornell would take part:

During his first few years in Massachusetts, Underhill performed well: he helped capture the miscreant Christopher Gardiner; escorted the governor on visits to settlements outside of Boston; traveled to England to solicit donations of arms for the colony; and raised a surprise alarm to demonstrate the lack of military preparedness among the general colonists,…

Note: Underhill did not capture Christopher Gardiner. Indians found Gardiner’s hut in the wilderness and asked Plymouth Governor Bradford if they should kill him. He asked them to capture him instead, which they did. Underhill and his Lieutenant collected Gardiner from Plymouth.

It would not take long for Underhill, though, to become disenchanted with the colonies, and then turn against them:

Underhill’s attraction in 1636-37 to the nascent antinomiam movement had political and social, as well as religious, dimensions. As a General Court deputy and political observer in the early 1630’s, Underhill must have been aware the other men besides himself were dissatisfied with the seeming lack of respect they received in the Bay Colony.

The Antinomiam Controversy consumed John Underhill, Anne Hutchinson, her brother-in-law John Wheelright, John Coggeshall, Henry Vane (Governor) and many others at the same time the colonists would set out to massacre a Pequot Indian village. One can only wonder at the impact these events would have on the young Sgt William Cornell.

As noted, William Cornell was one of probably handful of soldiers from Roxbury (History of Norfolk County, Massachusetts, 1622-1918, Volume 1) to fight in the Pequot War. This war brings Cornell the soldier into alliance with many local Indian tribes, as they fight their way to the Pequot village at Mystic and then fight their way back home:

The white settlers of New England made common cause against the Pequot. Roger Williams enlisted the cooperation of the Mohegan Chief Uncas, with seventy of his warriors; Capt. John Mason of Hartford raised a force of ninety men; Captain Patrick of Plymouth recruited a company of forty volunteers in that colony; and Captain Underhill took twenty men from the Massachusetts Bay settlements, about one–half who went from the Norfolk County.

If this is accurate only 10 men under Captain Underhill came from Boston, Dorchester or Roxbury. And one of these was Sgt William Cornell.

I should note that enlisting the Mohegan Sachem Uncas was not great feat. Uncas was the son-in-law of Sassacus, the Sachem of the Pequots. Uncas had broken with the Pequots, creating a civil war between his newly formed Mohegans and his old tribe the Pequots. The Pequot War – in reality – was the result of Uncas convincing the English Settlers and Narangasett Indians to obliterate his political rival.

A good and brief description of what transpired is this:

Mohegan oral tradition holds that the Mohegan-Pequots, originally the same tribe, migrated into the region some time before contact with Europeans. Anthropological evidence shows that the two groups were very closely related. Just before the outbreak of war with the English, the Mohegans under a sachem named Uncas split from the Pequots and aligned themselves with the English.

At the time of the Pequot War, Pequot strength was concentrated along the Pequot (now Thames) and Mystic Rivers in what is now southeastern Connecticut. Mystic, or Missituk, was the site of the major battle of the War. Under the leadership of Captain John Mason from Connecticut and Captain John Underhill from Massachusetts Bay Colony, English Puritan troops, with the help of Mohegan and Narragansett allies, burned the village and killed the estimated 400-700 Pequots inside.

The massacre had a lasting effect on the Indian allies of the English.

During the Pequot War of 1637, the Narragansett allied with the New England colonists. However, the brutality of the English in the Mystic massacre shocked the Narragansett, who returned home in disgust.[9]

They would never trust the English again, and the realization Europeans would slaughter a village of unarmed people was disturbing, to say the least.

The Pequot War also found English soldiers like Cornell fighting alongside Narangasett Indians.What bonds this kind of experience can create is well known. Fighting side-by-side tends to break down social barriers and create brothers in arms.

One final note on the Indian aspect of this before we get back to William Cornell. The Sachem of the Narangasett who allowed the English soldiers to traverse his lands and attack the Pequots at Mystic was their Great Sachem Canonicus:

When Roger Williams and his company felt constrained to withdraw from Massachusetts Bay Colony, they sought refuge with the Narragansett tribe at a place that is now part of Providence, Rhode Island, where Canonicus made them welcome.[2] In 1636, he gave Williams the large tract of land which became the first nucleus of the colony of Providence Plantation. In 1637, Canonicus was largely responsible for the Narragansetts’ decision to side with the English during the Pequot War.

I have to note now that Canonicus was allegedly the grandfather of Mary Hyanno.

Also Known As: “Yanno/Thannough”, “(Thyannough)” Birthdate: Birthplace: Cape Cod, Barnstable, Massachusetts, United States Death: Died in Mattachee Lands (Present Barnstable County), (Present Massachusetts), (Present USA) Place of Burial: Cummaquid, Barnstable County, Massachusetts, United States Immediate Family: Son of Conanicus Hyanno and Thyannough Hyanno

Husband of Princess of the Narragansitts

Father of Chief John Hyanno

Mary Hyanno’s father is Chief John Haynno – listed here at the bottom. His father was Sachem Iyanough (to whom this record belongs). Iyanough’s wife was a Princess of the Narragansitts, daughter to Canonicus – Great Sacham of the Narangesetts. However, this lineage may be suspect (see final post in this series).

Canonicus would know of any great deeds by individuals in the Pequot War – English or otherwise. Is it possible Sgt William Cornell’s acts created Indian allies at all levels of Indian society? It is not impossible.

Some time after the Pequot War, Sgt. William Cornell moves away from Roxbury. His first wife has died at some point. Apparently he too has tired of the Bay Colony. He does not move to Rhode Island, probably because the religious views of Roger Williams, John Coggeshall and Anne Hutchinson are too far from his own. So instead he begins a westward migration.

In early 1638 we find William Cornell somehow attached to Fort Saybrook, as noted in this testimonial on the purchase of lands from the Indians for the towns of Stradford and Bridgeport:

“That in the beginning of the year 1638, the last week in March Mr. Hopkins and Mr. Goodwin,* being employed to treat with the Indians and to make sure ol that whole tract of land in order to prevent the dutch and to accommodate the English who might after come to inhabit there, I was sent with them as an interpreter (for want of a better) we having an Indian with us for a guide, acquainted the Indians as we passed with our purpose and went as far as about Narwoke before we stayed. Coming thither on the first day we gave notice to the Sachem and the Indians to meet there on the second day that we might treat with them all together about the business. Accordingly on the second day there was a full meeting (as themselves sayd) of all the Sachems, old men and Captaynes from about Milford to Hudson’s River.

“It being moved among them which of them would go up with us to signific this agreement and to present their wampem to the Sachem at Coneckticott, at last Waunelan and Wouwequock Paranoket, offered themselves, and were much applauded by the rest for it. Accordingly those two Indians went up with us to Harford. Not long after there was a comilee in Mr. Hooker’s barne, the meeting house then not buylded, where they two did apeare and presented their wampum, (but ould Mr. Pinchin one of ye magistrates there then) taking him to be the interpreter, then I remember I went out and attended the business no farther, so that what was further done or what writings there were about the buysness I cannot now say, but I supose if search be made something of the business may be found in the records of the Court, and I supose if Mr. Goodwin be inquired of he can say the same for substance as I doe and William Cornwell at Sebrook who was there.”

Reference: “A History of the Old Town of Stratford and the City of Bridgeport, Connecticut“ by Samuel Orcutt, 1886.

It is not clear whether William Cornell had left the militia or not in the early part of 1638 at the time of these meetings. It is interesting, thought, he is not referred to as “Sergeant” in this document. But this testimony was recorded some 20 years after the event mentioned, well after he left the service of the militia.

Whatever his military situation, this was an amazing meeting of Sachems, Captains and Wise Men in the area. Not just anyone is called to these kinds of negotiations.

I must also note the return of a name from Cornell’s days at Roxbury, MA: “ould Mr. Pinchin” has to be William Pynchin, founder of Roxbury and many other towns in New England:

William Pynchon (October 11, 1590 – October 29, 1662) was an English colonist and fur trader in North America best known as the founder of Springfield, Massachusetts, USA. He was also a colonialtreasurer, original patentee of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and the iconoclastic author of the New World’s first banned book. An original settler of Roxbury, Massachusetts, Pynchon became dissatisfied with that town’s notoriously rocky soil and in 1635, led the initial settlement expedition to Springfield, Hampden County, Massachusetts, … In 1636, he returned to officially purchase its land, then known as “Agawam.” In 1640, Springfield was officially renamed after Pynchon’s home village, now a suburb of Chelmsford in Essex, England.

Again we are drawn back to Essex, England! I do not think these are coincidental associations, but the normal alliance of kindred clan and views. A common thread is running through these associations of William Cornell’s. One which William Pynchin reflects:

By founding Springfield where Pynchon did, much of the Connecticut River’s traffic would have to either begin, end, or cross his settlement. Additionally, the land that would become Springfield was inarguably among the most fertile for farming in New England — and its Natives were initially friendly, unlike those near southerly Connecticut River settlements such as Hartford.

Earlier settlers of the Connecticut River Valley — who then resided in the three Connecticut settlements at Wethersfield, Hartford and Windsor — had been primarily religious-minded and did not judge land for settlement in the shrewd terms that Pynchon did.

…

In founding “The Great River’s” northernmost settlement, Pynchon sought to enhance the trading links with upstream Native peoples such as the Pocumtucks, and over the next generation he built Springfield into a thriving trade town and made a fortune, personally. As noted above, after disagreements with Captain John Mason and later Thomas Hooker about how to treat the native population (Pynchon was a man of peace and Springfield’s natives were friendly, whereas Hartford’s natives were warlike and thus Connecticut’s settlers chose to treat them as enemies rather than friends.) Pynchon believed that Connecticut’s policy of intimidating and brutalizing natives was not only unconscionable, but bad for business.

So when colonists wanted to purchase the lands for the towns of Stratford and Bridgeport, they enlisted William Cornell of Seabrook along with his old neighbor from Roxbury: William, Pynchin. Men who apparently knew how to do business with the Indians in a fair and equitable manner.

The records then go on to show Sgt William Cornwell went on to become a founding member of Hartford CT the following year. Per the William Cornell biography “William Cornwall and His Descendants“, by Edward Everett Cornwall, 1901) the surveys of 1639 show him having:

… a house lot of eight acres in the village, ‘no. 54, west of South Street, south from the Lane’, which corresponds to a location near the north end of the present Village Street. One half his house lot lay in the ‘Soldier’s Field’, a choice tract which was divided among the veterans of the Pequot War.

Indeed, if you look at the founders of Hartford many are veterans of that war. Included in the list is Reverend Thomas Hooker.

Also are two members of another branch of my family that ends up marrying into the Cornwell lineage: Samuel Hale and Thomas Hale. Their sister Martha Hale marries Deacon Paul Peck in 1638 in Hartford, CT. Their daughter Martha Peck will go on to marry William Cornwell’s oldest son – Sgt. John Cornwell. Their daughter Mary Cornwell is listed 3rd in the line from William Cornell to myself in the lineage at the top of this post.

The Cornwell’s do not stay long in Hartford, possibly again because of the positions of Rev Thomas Hooker and others.

By 1650 (or earlier) William Cornell and his family help found Middletown, CT about 15 miles south of Hartford. What is interesting about this town (known previously as Mattabeseck) is that it was the center of the Wonguk Indians under Sachem Sowheag (or “Sequin”). In the late 1630’s there was much tension between the colonies and Sowheag. He too had refused to turn over Pequot Indians accused murdering colonists from Wethersfield. A similar act of defiance had precipitated the Pequot War. The order had even been given to send 100 soldiers to Mattabeseck to capture the accused killers. But for some reason this time war was avoided.

The settlement at Mattabeseck was considered as early as 1646, but for some reason went slowly and is recorded as being established in 1650. This recent article explains why there were probably colonists there before 1650:

“The 1650 date got into people’s minds because lazy historians had done enough work, and it was the only date anybody had,” said Kylin, a past master of St. John’s Lodge in Middletown and a doctoral candidate at the State University of New York at Buffalo. “If you think about it, a town would have to have been settled before anyone could make a town out of it, so Middletown had to have been settled before the General Court made it a town in 1650.”

Kylin said Middletown was settled beginning in 1643, and he points to a mention of the fledgling community in papers belonging to John Winthrop, the Puritan governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony.

What is fascinating about Mattabeseck, Sowheag and Cornell is they all share a common bit of land – Indian Hill. And it is this bit of land that makes one think William Cornell had something to do with the establishment of Mattabeseck/Middletown.

Indian Hill was where the Sachem Sowheag had his fort and residence:

Sowheig ruled over a large tract of country on both sides of the Connecticut River, including the Piquag or Wethersfield Indians, also a tribe on the north branch of Sebethe River in Berlin. The township of Farmington is supposed to have been part of his dominions.

He lived on Indian Hill. When he wished to assemble his braves for council or war, he would stand on the hill, and blow a powerful blast on his wondrous horn or shell, which could be heard all over the surrounding country, and the fleet-footed warriors would soon come rushing in from east, west, north and south, in answer to the call of their mighty chief.

And this from Indian Hill Cemetery in Middletown, CT:

From the peak of the grassy hill … Sowheag, leader of the Wangunks, could see for miles, observing the round-topped wigwams of his people in small settlements on both sides of the Connecticut River. The Wangunks called this area Mattabeseck and here they grew corn, beans and sunflowers; fished; and hunted deer and smaller game.

About 1639, Sowheag and his people built a fortification on this hill, perhaps as a defense against other Native American peoples, perhaps also as a caution against English settlers who were moving steadily into Connecticut. Already, large numbers of Native Americans had died from diseases like smallpox, which the Europeans had brought.

…

English settlers began arriving in Mattabeseck by 1650, laying out their home lots on what is now Main Street. For Two decades, the two communities coexisted relatively peacefully. But when hostilities erupted between white colonists and Native Americans in other parts of New England, Middletown’s English families became uneasy that the Wangunks would reclaim their lands. Accordingly, in 1673, they officially purchased from the Wangunks the land already designated as Middletown, again establishing two “reservations” for the Wangunks to inhabit.

I note the date 1673. Because it seems William Cornell also owned land on Indian Hill, per is Last Will and Testament:

“I give to my son William Cornwell ten acres of my land upon the Indian Hill at the east end, the whole breadth of the lot, moreover I give to my said son one third part of my land yet to be divided by the list of 1674 on the east side of the river, the other two thirds of the aforesaid land to my sons Samuel and Thomas equally to be divided between them. I give moreover to my son Samuel one hundred acres of my wood lot at the Long Hill, the remainder to go to my son Jacob. I give moreover to my son Thomas what is aforesayd the remainder of my lott at the Indian Hill, the ten acres as above mentioned being taken out of it.

William Cornell died in 1678. The Wangunks sold their final lands in 1673. There is mention of a “land yet to be divided by the list of 1674″, which sounds to me this may be a share of the Wangunk land to be apportioned. But the sale of 1673 was more to allocate lands to the Indians, than hand deed to the colonists. So I believe William Cornell had some special privilege to land on Indian Hill. A privilege that probably stretched back to when the town was first established, and the Wangunks allowed a settlement so near their tribal center.

What reason would William Cornell have for such distinction? Was it he had, through marriage to an Indian Princess who could trace her lineage back to the Narangesetts and Nausets, some special association? Is that why he was called to participate in negotiations for Stratford and Bridgeport with all the great Sachems and Indian leaders of the area?

Finally, we will touch on Mary Cornwall, as a segue to the next post (the Indian perspective of these times). I ran across this record recently and cannot fully decipher its meaning. It shows Mary Cornwall receiving”full communion” in 1678, near the end of her life (and William’s). It is listed on Ancestory.com as a ‘baptism’, but that seems to be a record error.

Here is the record (retyped from the original)

And here is the Ancestry.com view

There are other wives of “Cornwall” men receiving full communion in this record in Middletown, CT. But one has to wonder if this was maybe a late conversion to Christianity? More investigation might provide some insight. But at this point I end the discussion of William Cornell and turn to Mary Hyanno, and the power struggles that tore into the tribes of New England in the 1600’s.

Pingback: Tracing Our Family To The 1600’s In New England, Part 4 | Our Family History