Updated 12/20/14 to add further evidence of a broad trade network emanating from Mattabessett/Middletown throughout Connecticut.

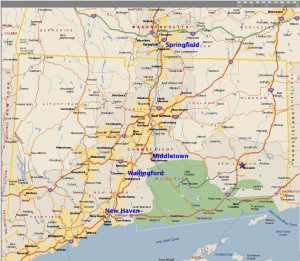

Updated 12/21/14 to add map showing how Springfield MA, Middletown CT and New Haven CT were connected by a portage site at Middletown.

Updated 12/21/14 to add record date for marriage between William Cornwell and Mary ____

Updated 3/28/15 and 5/16/15 to fix numerous typos.

Since this blog is dedicated to the genealogy of our family I want to step back and establish some context again. The lineage from my father back to Sgt William Cornwell (pictured above and my 10th great grandfather) is clear and unambiguous (see graph below – click all images to enlarge). This series of posts is still the story of one our of ancestors. A story I think my family would like to know. While it attempts to cover some research and explores some theories, it is – in the end – still a story of our family.

This second-to-the-last post in the series brings together a large pool of information, gleaned from numerous sources, to paint a more complete picture of the life of Sgt. William Cornwell (1609 – 1678). As we fill in these details we will discover that over the time of his life here in America, William Cornwell developed special relationships with some of the Indians of New England. We will see how a brutal war on a single tribe (called the Pequot War) affected English and Indians alike, and sent William Cornwell down and interesting (and profitable) path in life. It will postulate a relationship born of battles that founds a special town in Connecticut, and also leads me to conclude William Cornwell’s second wife was very likely an Indian.

In the last post of the series I will address the possibility William Cornwell’s 2nd wife was Mary Hyanno of Barnstable (a distinct possibility from her being Indian).

While I have researched numerous sources during this effort, I will rely mostly on the book “The Pequot War” by Alfred A Cave, 1996 for many of the references in this post. Cave’s research is extensive and covers most other sources I researched in any event. I will endeavor to reference the specific page when quoting.

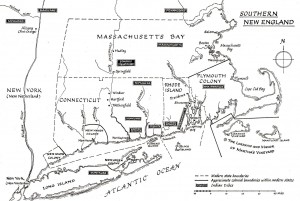

As I noted in the second post in the series, William Cornwell arrived in America around 1632-1633 and settled in Roxbury, MA. Roxbury was part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony Settlements (see map below).

William and his first wife (Joan Ranke) joined the church of Roxbury, which hosted as its “Teacher” the famous John Eliot. Eliot was among the vocal minority of Englishman who believed in co-existence with the Natives over conquest (e.g., Roger Williams who was banished from the Bay Colony due to his beliefs and established the Rhode Island settlements).

John Eliot performed missionary work with the Indians of what is now Massachusetts (which included both the Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay Colonies). He also established 7 Praying Towns for Christian Indians to assimilate into English society. These acts demonstrate his intention was clearly one of coexistence and not one of conquest. He was a vocal leader of William Cornwell’s first church in the new world, and he must have imprinted on Cornwell in some manner.

Roger Williams of Rhode Island was one of those who clearly practiced and preached coexistence, in his case with the Narragansetts. He noted the “sin” of the Indian way of life, but he had a tolerance for diversity that allowed him to live and trade with Indians without the need to annihilate them. As long as he lived, his Indian hosts/neighbors were able to live in peace on their lands.

But still in line with Puritan beliefs of separation between the English and Natives, even these leaders did not really live amongst the natives. The natives had their encampments, the English theirs. To truly intermingle was very rare in early New England.

The majority of the English colonists and their power brokers pretty much believed conquest was the answer to the Indians and gaining access to New England land, trade and resources. (The Pequot War; page xvi):

Puritan apologists justified their savagery by demonizing the victims. Contemporary chroniclers and later historians sympathetic to the Puritans painted a portrait of the Pequots as a “creull barbarous and bloudy” people. That portrait reflected a long-standing stereotype of the New World “savage” as irrational, unpredictable, malicious, treacherous and inhumane. Drawing upon a body of lore from the previous century that described Native American religious practices as a form of Satanism, Puritan writers declare that the Pequots were “the Devil’s instruments” and charged them with masterminding a plot to exterminate all Christians in New England.

…

We shall see, the Puritan explanation of the war will not stand close scrutiny.

After all my research on this period in history, I can easily see the effort to paint the Indians as devils – a clear propaganda campaign to cover for the brutal and “bloudy” acts of the English. It served as a way to rally support for “war” efforts that were really massacres and land grabs. It was a slander of the New England Indians that has taken centuries to undo.

This period in time, the 1630’s, was dominated by the Pequot War. It was the world that shaped young William Cornwell’s life. The reasons for the war play as much a part in Cornwell’s life as the war itself and its repercussions. To learn about William Cornwell,we must look at the world he traveled and understand this war.

I believe the motivation for the Pequot War was one of greed and resource-envy more than anything else (The Pequot War; page xxv):

Although the conflict cannot be explained in purely economic terms, it does not follow that the leaders were unmindful of the material advantages that would accrue to them after a successful campaign against Sassacus [Editor: Great Sachem of the Pequots] and his people. The records indicate that the magistrates were keenly interested in land, wampum, and Indian slaves, and they profited greatly from the Pequot War. Greed alone did not inspire the attack on the Pequots, but it was hardly absent and it was certainly not a deterrent.

Here I will disagree with Mr. Alfred A Cave.

I would agree it was not only English greed at work. But the Pequot War was primarily greed-driven. It is clear major leaders of the local Indians were also targeting the Pequots and their control over the lucrative fur, pelt and wampum trade. Uncas of the Mohegans wanted to claim leadership over all the Pequots (which he did in the end). The Narragansetts were weary of fighting the Pequots and wanted to break the Pequot hold on English trade (which also came to be). Sowheag of the Wanguks (the leader of the Connecticut River Indians) wanted to be freed of their Pequot masters so they could trade with whom they wished (which also happened).

As can be seen in the following diagram, Sassacus and his Pequots were surrounded by enemies both Indian and English. Pequots were the ones controlling the access to the wealth of the Connecticut River, the prime area of trade. The Pequot War broke this hold and provided much in return to all those allied against the Pequot. Leading up to (or paving the way for, depending on your perspective) the Pequot War it was the Indians and English of the Connecticut Valley who played pivotal roles. Without either one, the war effort would probably not even start.

See the 3rd post in this series for an overview of the Indian tribes of the region.

It may not be clear why I focus on Sequin/Sowheag, the grand Sachem of the Connecticut River Valley Indians, when telling William Cornwell’s story. It is because I believe Sequin/Sowheag is one of the grand chess masters in this period of turmoil. He appears (from the records) to be a friend and ally of William Cornwell (who settles and raises his family as a neighbor to this intriguing Indian Chief). Sequin’s/Sowheag’s story is one of those under-reported parts of our history. A story that was an example of mutually beneficial English and Native coexistence. A successful alternative to the powers-to-be of that time. A story those “Powers” probably wanted to hide from the pages of history in order to retain their power and control.

Sequin’s/Sowheag’s part in our story begins in 1626 with his tribe’s loss to the Pequots (The Pequot War; page 38):

In 1626 a Dutch chronicler reported that Pequot war parties had defeated the Wanguk sachem Sequin, leader of a loose alliance of River Indian bands, after “three desperate pitched battles”. The Connecticut valley Indians thereafter paid annual tribute to the Pequot grand sachem and received a pledge of Pequot protection.

We begin our journey with this powerful and intelligent Indian Chief under a forced tribute relationship with the Pequot – who basically require payment from Sequin’s/Sowheag’s profitable trade on the Connecticut River. An arrangement Sequin/Sowheage attempts to break many times.

By 1631 Sequin/Sowheag sends his son Wahginnacut to both Boston and Plymouth to invite the English to settle on the River (and of course loosen the Pequot hold over the Wanguks). This is a smart idea, because Indians allied with the English tend to be immune from power grabs by other tribes (see the 3rd post in the series on early Wampanoag and Narragansett frictions surrounding the establishment of Plymouth). Initially the English decline his offer, but after some time they are setting up settlements at Hartford, Wethersfield and Windsor (The Pequot War; page 84):

Accordingly … the General Court in May and June of 1635 granted the inhabitants of several towns permission to emigrate “provided they continue under this government.” Shortly after, settlers from Dorchester, as noted earlier, settled near Plymouth’s trading post on the Connecticut River, founding the town of Windsor. A handful of emigrants from Watertown established a crude settlement near the site of the future town of Wethersfield.

… On May 31, 1636, Winthrop wrote in his journal, “Mr. Hooker, pastor of the church at Newton, and most of his congregation, went to Connecticut. … Hooker and his people founded Hartford”.

According to “The Colonial History of Hartford: Gathered from the Original Records”, by William DeLoss Love, 1914, the Indians whose land the English settled on all belonged to Sequin/Sowheag or his son Sequassen. It took a few years, but Sequin/Sowheag got his English neighbors (which also implied by way of Indian culture some form of joint protection).

So here we have the River Indians selling land to the English in the heart of the rich river valley EVERYONE wants to control. River Indians who are not only enemies of the Pequot (and the Mohegans) with whom they want independence, but through Sequasson they are also allies by marriage to the Narragansett.

Massecump was a son of the Narragansett sachem Miantonomo and a brother of Canochet. Love speculates that his mother could have been Wawarme, daughter of the Wangunk leader Sowheage.

It was these three isolated English Settlements on the Connecticut River that created the fear of the Pequot inside English plantations – a self fulfilling prophesy. Why else put so many English at risk so far into the interior? (see map below for the location of these settlements relative to Boston and Plymouth):

Events pretty much unfolded as one would expect with escalating incursions and insults, followed by localized bloodshed, and then finally all out war and the necessary annihilation of the Pequots. Or so we are told by the Powers-that-were. It may be that what really transpired was more complex and planned out than recorded by history.

A very interesting event occurred that lit the flames of war on the Pequot nation. When Sowheag attempted to execute his rights in the newly settled town of Wethersfield and set up his home next to the settlers, he was unceremoniously chased out of town. Chased from the lands HE sold to the English – sold with the express right given him to live there (among the English and away from the Pequot and Mohegans).

Sowheag would retreat to the Wanguk village of Mattabesset – the future site of Middletown where Sgt. William Cornwell would live out his life – about 20 miles south of Wethersfiled and roughly halfway to Ft. Saybrook.

The incident at Wethersfield was the tripwire for the Pequot War. When the English Settlers violated their agreement and chased Sequin/Sowheag off what was his rightful land, they voided the agreement of coexistence and co-protection. I am sure word got out (deliberately or otherwise) that the Weathersfield Settlers had run off the Grand Sachem of the Connecticut River Indians. To the Pequot, this schism must have looked like open season on English Settlers. They attacked, killed 9 and kidnapped two teen age girls.

Later the Wethersfield settlers would take Sequin/Sowheag to General Court for harboring those same Pequot Indians who attacked them. But to underscore how foolish the event was, the Bay Colony General Court sided with Sequin/Sowheag! They determined he was the one wronged by the settlers breaking their agreement with him. Clearly Sequin/Sowheag has some serious clout in the region with both the Indians and English. Was this evidence of a planned and expected conflict?

This is also the period (1631-1636) when Captain Underhill of the Bay C0lony stands up the militia there, including one Sgt William Cornwell of Roxbury (reference 2nd post in this series on the militia). It is Captain Underhill of Boston with his 20 men (including 10 from Roxbury with William Cornwell) who is sent to help Captain Mason (of Hartford) to destroy the Pequots.

Instead of repeating in detail here what happens during the war, reference the Chronology of the Pequot War for a blow-by-blow account. Note that when we see “Captain Underhill and his men” we are also seeing Sgt William Cornwell (being one of his top men).

In preparation for the main battle (or massacre) of the Pequots in their Mystic Fort, the English and their Indian allies all converge at Fort Saybrook. Underhill and his 20 men arrive from Boston. Captain Mason arrives with 70 citizen-soldiers from the Connecticut River Settlements. With Mason are the Mohegans under Uncas and “River Indians” under Sequin/Sowheag and his son Sequassen. Here they debate an attack plan, which takes strange twists and turns.

We have historic evidence the River Indians were actually pushing the English Settlers to war. It is in a comment by Rev Hooker before Mason departs (from “Mystic Fiasco How the Indians Won the Pequot War” by David R Wanger, Jack Dempsey, 2010; page 9 – describing the mood at Ft. Saybrook):

The unproven Mason cannot get the voices of Hartford’s leaders out of his mind. “though we feel neither the time nor our strength fit for such a service,” says the Reverend Hooker, “yet the Indians here our friends [around Hartford] are so importunate with us to make war presently that, unless we attempt something, we deliver our persons into contempt of base fear and cowardice; and cause them to turn enemies against us“.

As we know, those Indians around Hartford were part of Sequin’s/Sowheag’s realm under the Sachem of his son Sequassen. Clearly there is more than a little pressure on those isolated English settlements to move on the Pequots by Sequin/Sowheag.

Editor’s note: I was nearly finished with this post when I picked up the above book and read it. Cave’s book is better in my opinion, but the authors of this second book really do a good job of shredding the accounts of Captain Mason (who would become Governor based on his “war hero” status) and Captain Underhill (who is exiled much like Roger Williams). The authors do this by physically retracing the march from the lands of the Narragansett to the place where the English are rescued after the pitched battles. They prove how much fiction there really is behind the original accounts of this war by Mason and Underhill.

The authors also lay out a strong case that the Pequots were not massacred, but actually retreated into the wilderness when their scouts detected the bumbling English marching to Mystic Fort (blindly led by their Indian allies). The fact is the “military expedition” was not even planned or prepared for. 90 men just got in a boat and made it up as they went along in a wilderness they knew nothing about. It is amazing they even found their way back out. The authors make the case the Pequots left a diversionary, small force at Fort Mystic to distract the English and lure them into Ambush. It almost worked.

The Pequots, they claim, simply melted into the wilderness and other tribes – many to return as Mohegans under Uncas. This claim is well founded by records of the time. What I wrote from here on was written before I read the book. – End note

From a site dedicated to the Pequot War, we know Sgt William Cornwell sets outs with one or both Sachem’s of the River Indians (both are listed as participants) to land in Narragansett. Here the English ask for passage over land to the Pequot’s Mystic Fort. Recall the Sachems of the Narragansett are allies through marriage with the River Indians, which may be the reason that not only is permission given, but a force of Narragansett’s join the combatants.

Now if one thinks about this for a moment this “last minute” change of plan and last minute invitation to war would seem insane on the face of it. The Narragansetts would not hasten to war after a few days’ discussion unless there was a dear and trusted ally making the case. The English were surely not a dear and trusted ally in the minds of the Narragansett Sachems. So they could not invoke a major war effort at the last minute. And neither were the former Pequots under Uncas (who would later make war on the Narragansett and the Wanguks).

No, in my mind it had to be Sequassen who brought along the Narragansetts (and maybe had this all planned out ahead of time). History claims Roger Williams played a major role in the alliance (and reported as such to keep in good favor with Boston and Plymouth). But there is no mention of his involvement in these last minute decisions and I just don’t think even Williams could convince the Narraganset to open a major war along their western boarder with an enemy that had cost them so dearly not too many years prior.

So onto battle go the Narragansett, the Wanguks and the Mohegans – bringing along the English soldiers who are more their secret weapons than anything else. To understand how much the English were being led around, the English did not even know how to find Mystic Fort! They were lost in the wilderness and end up sweltering under the heat without proper provision or even a supply chain set up. If not for the Indian allies leading the way, the Mystic Massacre would not have taken place due to a simple lack of English knowledge on how to get there over land from Rhode Island!

I do not believe the River Indians understood what they would finally reap by unleashing the English on the Pequots. I think that is the part of the plan the Indians did not have a good handle on.

Once the forces arrived it was a “bloudy” massacre, as the English set wigwams afire and then sealed off all avenues of escape. As is told in the record of Fort Mystic, the Indians allied with Mason and Underhill stood back during the “attack” – many aghast. Indians did not tend to wipe out non-combatants (but they did take them for slaves – basically less brutal but not innocent). The battle of Mystic was followed by years of hunting down and slaying hundreds of Pequot Indians. Indians not doing anything but living their lives.

The massacre does seem to have separated the victorious allies into two camps: those who would reject conquest in the future and those who would follow it to the end of their days. This happened on both sides, Indian and English. Those bent on conquest killed each other off, a culling that did not end until King Phillips War in 1675.

Mason and Underhill would go on to be Indian Fighters, penning zealot-dripping accounts of the Pequot War. Mason’s account looks to have a ghost writer whose flourish and barn-burning rhetoric had to be that of Hartford founders Reverend Hooker or Reverend Stone. Those bent on conquest (Mason, Underhill and Uncas) all have monuments erected to their glory. As the saying goes, the victors get to write the history (initially).

Those who preferred coexistence are barely seen in the records of that time – and onwards. Its as if the chroniclers of that time had no interest in the people who shunned war and conquest. This includes Sequin/Sowheag, Sequassen and Sgt. William Cornwell – all who seem to disappear in the written, contemporary record. If one looks at who really reaped the rewards though, one Sgt William Cornwell seems to acquire more land than any other English combatant of the war. And Sequin/Sowheag ends up the one controlling the trade of the Connecticut River.

How is that possible?

After the war William Cornwell spends some time at Ft Saybrook, where he apparently supports negotiations for Indian land to create the town of Stratford (reference post 2 in this series for the details).

He then shows up very briefly in Hartford due to his part in the Pequot War. His land grants are in town at a very prestigious location. There for a brief time his neighbors are Captain John Mason, Reverend Hooker and many others – basking in their glory of the Pequot War.

Apparently this is too much for William Cornwell to live with. There is supposedly a document that indicates Cornwell moves from Hartford – on the West side of the river – to “Hocanum” on the east side. I have not been able to find the document, but Hocanum was a village under the Wanguk tribe.

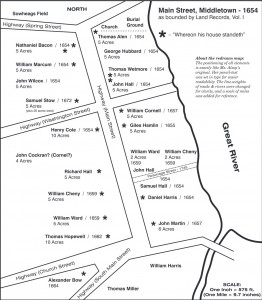

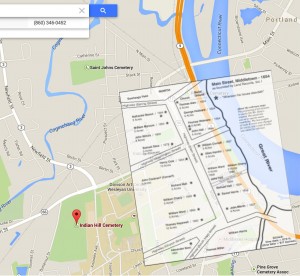

We next find William Cornwell at the Mattebessett Indian village where Sequin/Sowheag has his family and his fort. Cornwell’s lands at Mattebesic (renamed to Middletown two years after being incorporated) are extensive. He has 5 acres in the middle of town right on the river (see map below, original source here)

But note the land grant is from 1654 – even though Cornwell was living there much earlier. Also note the location of “Sowheag’s Field” at the very top of the map, at the North end of Main Street.

Sowheag had a famous fort on “Indian Hill” nearby.

Sowheig ruled over a large tract of country on both sides of the Connecticut River, including the Piquag or Wethersfield Indians, also a tribe on the north branch of Sebethe River in Berlin. The township of Farmington is supposed to have been part of his dominions.

He lived on Indian Hill. When he wished to assemble his braves for council or war, he would stand on the hill, and blow a powerful blast on his wondrous horn or shell, which could be heard all over the surrounding country, and the fleet-footed warriors would soon come rushing in from east, west, north and south, in answer to the call of their mighty chief.

This next image identifies Indian Hill (red arrow) relative to the original layout of Middletown:

In William Cornwall’s will it states (reference William Cornell biography “William Cornwall and His Descendants“, by Edward Everett Cornwall, 1901):

I give to my son William Cornwell ten acres of my land upon the Indian Hill at the east end, the whole breadth of the lot, …

I give moreover to my son Thomas what is aforesayd the remainder of my lott at the Indian Hill, the ten acres as above mentioned being taken out of it.

Notice how Indian Hill is outside the original town and supposedly own by by the Wanguks and Sequin’s/Sowheag. Yet William Cornwell seems to have well over 10 acres of that hill in his name by 1678. There are records of his land grants in downtown Middletown (1654) and in Newfields (1671) (Reference).

But nothing about Indian Hill?

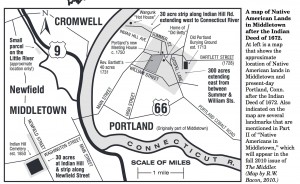

Here is a fascinating map showing the Wanguk Indian lands after the 1671 formalization defining which land was Indian and which was Middletown (Reference):

This shows that the entirety of Indian Hill is 30 acres! It would seem most if not all of Indian Hill was finally “owned” by William Cornwell to give in his will. All in all, William Cornwell has 903 acres in and around Middletown at the time of his death.

So when did William Cornwell actually move to the Indian village of Mattebessett alongside Sequin/Sowheag, his Brother-in-Arms from the Pequot War ?

As I promised in post 1 of this series I will follow the genealogical creed of citation of record as the foundation of my analysis. I am going to reference the Middletown vital records from Ancestry.com: White, Lorraine Cook, ed. The Barbour Collection of Connecticut Town Vital Records. Vol. 1-55. Baltimore, MD, USA: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1994-2002. I am also going to assume a man of William Cornwell’s stature in the town would ensure his records were accurate and correct. If we assume this, we found some interesting facts.

8 of William Cornwell’s 9 children were born before 1651 – supposedly the year he “settles” in Mattebessett. However, every single birth record faithfully shows each one of these children was born in “Middletown”. If we take this as accurate – and we have no reason not to for 8 different births – it means William and Mary Cornwell were living in the Indian village of Mattebessett a full decade before the English town was established!

Another interesting fact is the timing and events of Middletown’s transition from Indian Village to Connecticut Town:

Sowheage allowed Connecticut Governor John Haynes to expand further into Wangunk country and eventually conveyed to colonial authorities a large tract of land. After Sowheage’s death in 1649, the General Court established the English settlement at Mattabesett (later renamed Middletown) and reserved two parcels of land for Sowheage’s descendants: one fifty-acre tract at Mattabesett and three hundred undefined acres at Wangunk.

It is Sowheag’s death that transitions Mattabessett Village into Middletown. It would explain a lot. It would explain how Cornwell was there so early, his massive land holdings – including lands on what were deemed Indian lands. He established Mattabessett as a trading center with Sequin/Sowheag, and after the Sachem’s death Cornwell helped evolve the Indian Village into a New England Town.

Here is my theory – which also has foundation in recorded fact.

After the Pequot War one of those disgusted with Puritan Zealots and their Conquest was Sgt William Cornwell. He had come to America and sat in John Eliot’s Roxbury Church, and I am sure he was preached on the concept of peaceful coexistence with the native Indians. He began is journey at Roxbury along with another purveyor of coexistence and trade: the founder of Roxbury, one William Pynchon:

William Pynchon was one of New England’s first and most business-minded settlers. In founding Roxbury, Massachusetts in 1630, Pynchon settled land near a narrow isthmus, which was necessary to cross in order to reach the Port of Boston — thus all of Massachusetts’ mainland trade needed to pass through his town. Unfortunately, Roxbury — originally named “Rocksbury” for its rocky soil — was a poor site on which to farm in comparison to the fertile Connecticut River Valley. Thus in 1635, Pynchon carefully scouted out the Connecticut River Valley for its best location to both farm and conduct business. Happily, he discovered that its best location had not yet been settled. In locating the land that would become the City of Springfield, Pynchon found land just north of the Connecticut River’s first large falls, the Enfield Falls, which was the river’s northern terminus navigable by seagoing ships. By founding Springfield where Pynchon did, much of the Connecticut River’s traffic would have to either begin, end, or cross his settlement. Additionally, the land that would become Springfield was inarguably among the most fertile for farming in New England — and its Natives were initially friendly, unlike those near southerly Connecticut River settlements such as Hartford.

…

In founding “The Great River’s” northernmost settlement, Pynchon sought to enhance the trading links with upstream Native peoples such as the Pocumtucks, and over the next generation he built Springfield into a thriving trade town and made a fortune, personally.

William Pynchon, in settling Springfield, pretty much controlled all trade north – which meant a good portion of the fur and pelt trade. His location was everything the settlers of Hartford, Wethersfield and Windsor thought they were getting. What Pynchon required was river transportation. And that is where William Cornwell and the Indian village of Mattebessett (Middletown) come into play. It turns out this location has a very special shipping feature:

Although the Dutch used the term broadly, specifically speaking, Mattabeseck is a place name for the location known today as Middletown, Connecticut. Linguistically, Mattabeseck is a regional variant of the same word as Mattapoisett, and means “land between waters”. It was used in both instances to indicate a place of portage. In this instance, the portage refers to the trail connecting the Quinnipiac River in Meriden to the Mattabeseck River (today known as the Mattabesset River[1]) in Middletown, and which subsequently links to the Connecticut River. In other words, travelling south on the Connecticut, at Middletown the river turns to the southeast toward the mouth of the Connecticut, but, by taking the Mattabesset River and then portaging (roughly along the route of today’s Route 66), one can connect to the Quinnipiac River and reach Long Island Sound at New Haven Harbor.

This ability to portage a short distance and bridge the Quinnipiac and Connecticut Rivers was a huge boon to anyone who knew about it. From here furs and pelts from Pynchon in Springfield could travel to Middletown, where some could be diverted to the Quinnipiac river (probably using Wanguk Indians as transport and traders) while the rest could go down the Connecticut and East to Boston. See map below for key locations:

One of the frictions between the Pequot (Dutch trade partners) and the Mohegans (English trade partners) was who would control the resources of the Connecticut River Valley. Sly old Sequin/Sowheag found a way to supply both England’s Massachusetts Bay Company and the Dutch West Indian Company from a single point!

This is by no means simple conjecture on my part (though it began that way). Living next door to William Cornwell in Middletown is one Captain Giles Hamlin, a well traveled mariner who provided shipping for Springfield, as well as a message courier for Boston and Plymouth. The fact he settles in Middletown and launches generations of Captains Hamlin is interesting to say the least. He has dealings with John Pynchon (William Pynchon’s son) at Springfield, Elder Goodwin of Hartford and John Crow of Fairfield. He could have set up shop in any of these places, but he chooses right next door to William Cornwell, friend and ally of Sequin/Sowheag, in Middletown.

The proof is in the results. Within 100 years Middletown, CT will grow to out-shadow all:

During the 18th century, Middletown became the largest and most prosperous settlement in Connecticut. By the time of the American Revolution, Middletown was a thriving port, comparable to Boston or New York in importance, with one-third of its citizens involved in merchant and maritime activities.

It seems quite clear that Sequin/Sowheag had a rare piece of land where his people could distribute trade east and west – and the English in Boston would not be the wiser. I suspect shipments from Springfield stopped regularly at Middletown where some goods would be diverted east to the Dutch. If Wanguks were used as the sales point to other tribes and locations, Middletown would control trade and wampum. The Wanguks would become powerful and rich, and so would the English.

We can look back and see the result of this probable alliance of Indians and English who practiced coexistence and trade. And from this we can further ponder how William Cornwell solidified such an arrangement with the Grand Sachem of the River Indians. There is no reason to assume it was no different than any other place in America during these early colonizing periods – through marriage.

Update (12/20/14): I continued to research the concept of a major trade center at Mattabesset Indian Village prior to the establishment of the Connecticut Town of Mattabesset (later Middletown). This trade center would exploit the portage trail between the Connecticut River and Quinnipiac River found at Mattabesset.

I wanted to find some 17th century connection between Middletown and current-day Meridan CT – where the Middletown portage and local streams and rivers finally entered the Quinnipiac. A connection between families would add great weight to my theory concerning the trade alliance between Sequin/Sowheag, Cornwell and Pynchon. At the time Meridan was actually part of Wallingford CT, and so I began there.

Amazingly, I did find such a connection in the form of one John Hall of Wallingford (reference: “John Hall of Wallingford, Conn“, James Shepard, 1902). There is a John Hall also in Middletown, and this is what the author has to say about him:

Savage and D. B. Hall both agree that John Hall 01 Middletown, came from Roxbury, Mass. The Report of the Record Commissioners, in their Roxbury record p. 4, under date between 1636 and 1640, gives a list of the inhabitants of Roxbury in which is the name of John Hall, having 12 acres of land and 4 persons in the family. His name also appears with the prefix Mr. in Elliott’s church records of Roxbury. Ellis’s History of Roxbury gives the date of the list of Roxbury inhabitants as certainly after 1638 and before 1640. Memorial History of Boston p. 407, gives the date for this list as 1639.

This author also finds a connection to a John Hall of Hartford who fought in the Pequot War, but on some very shaky arguments dismisses him as being the same John Hall from Roxbury and later Middletown:

In the Hartford division of land of 1639, (so called) one John Hall had six acres of land given him by courtesie of the town. This fact in connection with the grant of land from the Colony for services in the Pequot war, would be conclusive that John Hall of New Haven was the original settler of Hartford 1636, who had land in the distribution of 1639, and that he went to the war from Hartford with Captain Mason, were it not for the fact that the Rev. David B. Hall in his Halls of New England, 1883, i and others following him), assert that John Hall of Middletown, Conn., was the original settler of Hart ford,

…

In the absence of any record or proof to the contrary we would presume that the Pequot soldier of 1637, to whose son the colony of Connecticut gave land in compensation for this service, enlisted from Connecticut, and the original settler of Hartford is where we would naturally expect to find the John Hall of the Hooker party.

The author wrongly assumes that if someone was to have been granted land in Hartford for service in the Pequot war, it meant that person had to be from one of the River settlements. Of course this is wrong – as proven by William Cornwell himself. It is very likely John Hall of Roxbury was part of Captain Underhill’s militia along with Sgt William Cornwell, and was also granted land in Hartford and later moves to Middletown. What is interesting is the Hall family then migrates from Middletown to Wallingford and become rich in the trade business.

Given that this one baseless assumption underpins all the erroneous conclusions throughout the book, it is not unreasonable to assume the John Hall of Roxbury is the same as the one in Hartford, as the one in Middletown. Then by extension, the John Hall later of New Haven and then Wallingford is the one and a same person. Which brings us to the connections:

“During his thirty years residence in New Haven, John Hall witnessed the evolution of a thriving commercial town from the little colony he had assisted in planting in the midst of an unbroken wilderness. What he was engaged in during all these years, to provide means for the support and education of his growing family, we do not certainly know, …. From the fact of his name appearing so infrequently upon the records and his not occupying any public position, it would appear that he was absent much of the time from New Haven … The probable inference from these facts, is that John Hall was in trade, perhaps with the Indians for furs, and that later on his ventures required his absence much of the time from his home. This accords with the supposition that he explored the Connecticut country with John Oldham, and after wards conducted a second expedition thither for the purpose of trade, …

It is not known what he did, but by inference it was trading with Indians. It seems so obvious that the Halls of Middletown ended up in New Haven, where the Quinnipiac reaches Long Island Sound (and access to New York). This was the logical trade path using the portage at Middletown. And later the family moves to Wallingford, the exact location where the portage and river/stream path enters the Quinnipiac.

Coincidence? Not likely. Nor is this family connection to Cornwell:

Davis’ History of Wallingford, 1870, erroneously gives John Hall a son Richard, born July 11, 1645, but there is no birth or baptism of any such son. There was a Richard Hall at New Haven who died Feb. 3, 1725-6,- age 54, leaving a widow Hannah, and children, as stated by Davis, excepting that his son John was born in 1704, instead of 1714. This Richard Hall, however, was not born in i645, as stated in Davis, but in 1672 as shown by the Middletown records and by his tomb stone which, with that of his wife, Hannah, stands by the west wall in the Grove Street Cemetery at New Haven. (New Haven Historical Society Papers, Vol. iii, p. 526. ) He was the son of Captain John3 and Elizabeth (Cornwell) Hall of Middletown, (Richard,2 John.1 ) His first deed of land in New Haven is dated May 7, 1703. In this deed he is de scribed as “Richd Hall of Middletown, * * * now Resident in new haven, marriner,” …

Elizabeth (Cornwell) Hall of Middletown was the daughter of William and Mary Cornwell. From these facts I would say we have firm evidence of an extensive trading empire created by the alliance of these Pequot War veterans with Sowheag/Sequin of Mattabesset. A trading empire that spread from Springfiled (Pynchon) to Middletown (Cornwell/Hamlin/Hall) to New Haven (Hall) – and all ports east and west.– end upate

Mary Cornwell

We have some tantalizing hints in the records about William’s second wife. For some strange reason the records of Middletown never have a maiden name for Mary, a woman who lived in the town for 35+ years! Now we know the first years’ of the records were lost, but that leaves 25+ years to sort out with the preeminent founders and their children what William Cornwell’s wife’s maiden name was. It could be the name was deliberately not provided, so as to not draw attention to her status.

Update: In another odd example of a record being vague and precise at the same time, we have the dates of William Cornwell’s marriages from the records of Middletown. The source from Ancestry.com is: Torry, Clarence A. New England Marriages Prior to 1700. Baltimore, MD, USA: Genealogical Publishing Co., 2004. Here is a screen snap of the translated original record:

Note some fascinating aspects of this record. Neither wife’s maiden name was recorded (we know the first wife was Joan Ranke from English records). It seems Joan Ranke may have made it to both Hartford and Middletown before she died (if I am interpreting the citations at the end correctly. As for Mary, we have the year of her marriage as 1639. What surprises me is the listing of Roxbury as a location for her. Did William go back to Roxbury after Joan passed? Is this the window for him to meet someone from Cape Cod? Or is this an error?

What we do know is 1639 puts the marriage into a reasonable range for the supposed Mary Hyanno to be married. If she existed at all, she would be between 18 and 17 (assuming a birth date between 1622-1623) – end update

And as noted in the second post of the series: Mary is apparently provided full communion two days after Williams death:

Here is the record (retyped from the original)

And here is the Ancestry.com view

Is this so she would be legally recognized in terms of William’s will? Was it a deathbed request? All the other entries are for her children and grand children and communion is at a very young age. Not for her.

Is this so she would be legally recognized in terms of William’s will? Was it a deathbed request? All the other entries are for her children and grand children and communion is at a very young age. Not for her.

If you combine these facts with the fact William Cornwell bequeathed Indian land (per 1672 records) on Indian Hill to his sons (in 1678), it seems obvious he was married into Indian society and was considered owner of Indian Lands.

How else could the site of Sachem Seqin/Sowheag’s home and fort be willed by Cornwell without a peep from the Wanguk leaders still living across the river?

Pingback: The Dorsey’s Of Norfolk & Annapolis | Our Family History