Updated 12/22/14 to fix spelling of Indian tribe names

Updated 1/1/15 for corrections to Iyanough/Hyanno generations plus other editorial clean ups

In this post I hope to provide context with respect to the New England Indians during the period 1630-1640. This is the window in which William Cornell comes to Roxbury, MA, joins the Roxbury militia, at some point loses his first wife, fights the Pequots and then moves to Hartford, CT by 1639 where he is recorded having property. It is inside this window of time a nexus must be shown between Mary Hyanno and William Cornwell for the claim of Hyanno Indian lineage to be true.

To set an end state for this post, it must be noted that the first child of William and Mary Cornwell (i.e, Sgt. John Cornwell) was born in 1840 in Middletown, CT (reference: White, Lorraine Cook, ed. The Barbour Collection of Connecticut Town Vital Records. Vol. 1-55. Baltimore, MD, USA: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1994-2002; via Ancestry.com and Family Research Connecticut Town Birth Records, pre-1870 (Barbour Collection) [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA).

Therefore if Mary Cornwell is actually Mary Hyanno, then William Cornwell must meet her sometime in this period. Since no record exists of this meeting, it can only be inferred by events in the region that could tie the Hyanno and Cornwell families together.

Unfortunately, Indians did not keep a written record of their history or genealogy. So even the existence of Mary Hyanno has been challenging to prove (outside the Bearse-family claims). But assuming she did exist, and assuming she is the daughter of John Hyanno, Sagamore of an Indian village located in Barnstable, MA, then we must explore this tribe and how it evolved from the time of the first Thanksgiving (which was attended by Mary’s grandfather Sachem Iyannough).

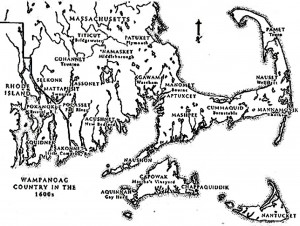

The map above will be used extensively to discuss the key New England Indian tribes, their power struggles and their basic struggle to survive during this time.

The Cummaquid and Nauset

As noted in Part 1 of this series, the Iyanough/Hyanno village at Cummaquid Harbor (now Barnstable Harbor) was part of the broader Nauset Indian Tribe, which extended all along Cape Cod. The Nauset were an independent tribe until disease swept through the region and forced them to join forces under the neighboring Wampanoag:

The Nauset were never numerous. The original population was probably around 1,500 in 1600 before the epidemics. In 1621 there were about 500 Nauset, and this number remained fairly constant up until 1675.

…

Shortly after Columbus’ voyage to the New World in 1492, a steady stream of European explorers, fishermen, and adventurers began regular visits to the coast of New England. Located on a landmark as obvious as Cape Cod, the Nauset had contact with Europeans at an early date, but these first meetings were not always friendly. European captains riding the Gulf Stream home from the Carribean were often tempted to increase profits by the last minute addition of some human cargo. The Nauset soon learned from sad experience that the white men from these strange ships frequently came ashore, not for trade, but to steal food and capture slaves. More so than the neighboring Wampanoag and other New England Algonquin, the Nauset were hostile to Europeans, and when the French expedition under Samuel de Champlain visited Cape Cod in 1606, the Nauset were not friendly.

…

This experience made the Pilgrims suspicious of the Nauset, but through the intercession of the Wampanoag sachem, Massasoit, relations improved. Early in, 1621 a young boy wandered off into the woods from Plymouth and became lost. Found by a Nauset hunting party, he was taken to their head sachem Aspinet at his village near Truro. Upon learning Aspinet had the boy, the English arranged a meeting through Iyanough, the Cummaquid sachem. Relations were still tense, but after an exchange of apologies and payment for the corn taken in November, Aspinet returned the boy. A warm friendship developed between the Pilgrims and Nauset, and during the winter of 1622, Aspinet is believed to have brought food to Plymouth which saved many from starvation. In the beginning, English settlements did not intrude into the Nauset homeland on Cape Cod. The exception being the small community started at Wessgussett in 1622. Unfortunately, this was probably the source of an epidemic which swept through the Nauset in 1623 killing both Aspinet and Iyanough.

This Iyanough, who dies in the swamps of Cape Cod, was allegedly Mary Hyanno’s father,. He definitely is the same Iyanough who attended the first Thanksgiving at Plymouth in 1621. I read somewhere Iyanough’s son John Hyanno (and presumably Mary Hyanno) were raised by their grandfather until John could take over leadership of the tribe.

The Cummaquids were also known as the Mattacheese, Mattachiest or Mattacheeset Indians. All the Nauset’s were later known as the Cape Cod Indians or South Sea Indians. Both the Nauset and Cummaquid become merged into the Mashpee Indians over time as the English begin to settle Cape Cod.

Here is a map showing the localities of these Indian groupings in the early 1600 [click to enlarge all images]:

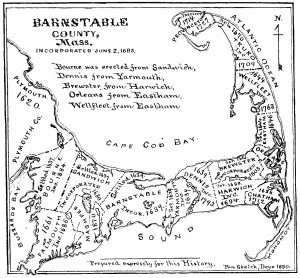

Moving west to east along the Cape we find the Mashpee, the Cummaquids and then the Nauset. The earliest history of Cape Code shows the area was beginning to be settled by the mid to late 1630’s – which is the time period we are interested in. The following map shows how the English settlements emanating from Plymouth came to being on Cape Cod:

For the Iyanough/Hyanno tribe at Cummaquid, the English began to develop towns among the Indian villages nearby very early:

- Sandwich MA settled 1637 (image above)

- Bourne MA settled 1637 (image above)

- Barnstable MA settled 1639 (image above)

- Yarmouth MA settled 1639 (image above)

- Mashpee MA established 1870

It is well recorded that as the English bought up lands from the Indians, and as the English numbers grew, many of the Indians moved to a reservation in Mashpee. This is one reason Mashpee is so late in becoming incorporated relative to other Nausett areas. According to “The Mashpee Indians: Tribe on Trial” (by Jack Campisi, 1991):

After the 1620s the Cape Indians were incapable of successfully waging war against the Plymouth Colony. The settlements that were made in the 1630’s came at what Jennings has appropriately called “widowed land” (1975). It is not coincidence that the settlements at Manomet in the 1620s and those of Sandwich, Yarmouth and Barnstable in the following decade occurred in areas that had been depopulated by disease.

English settlement continued well into the 1640s, when the public record shows the first mention of the Indians at Mashpee. In 1648 Paupmunnuck, “with the consent of his brother and all the rest of his associates,” sold a piece of land to Barnstable.

…

In theocratic Plymouth, churches were among the first structures to be erected and ministers were quick to seek conversion of the natives, a process made easier by their losses and dislocation … The solution was to bring these disparate remnants to a few locations and establish Christian Indian towns, … Mashpee suited this purpose admirably. It had a resident Indian population that remained largely intact through the early years of English settlement.

One can find reams of documentation on how Richard Bourne of Sandwich established a missionary to the Mashpee or South Sea Indians. So the question becomes how did this impact the Iyanough/Hyannos?

First off, while the Cape Cod or South Sea Indians where among the first to be converted to Christianity in large numbers, the leaders of the Indian tribes rarely participated. The european church and societal constructs were a threat to their power and prestige. So it is unlikely (but not impossible) that leading family members of the Cummaquid tribe would simply convert and marry into Puritan society early on.

Much of the conversion of the Cape Cod Indians to Christianity happened in the 1640’s and later. And it does not look like the Iyanoughy/Hyanno family was among the first to transition if we look at land transfers.

According to the “History of Barnstable County, Massachusetts: 1620-1637-1686-1890” (edited by Simeon L. Deyo, 1890) the Iyanough/Hyanno properties were some of the last to be sold in Barnstable. Beginning with the first settlement in 1639:

This was the Indian name [editor: Mattacheese] of lands, now in Barnstable and the northern part of Yarmouth, adjoining the ancient Cummaquid harbor. The lands of this township contained other Indian tribes at the south and west, each having a its sachem, by who the community was ruled. The names of the small tribes and their tracts were identical. Iyanough’s land and tribe was south – midway between the bay and sound; his name was often spelled Janno and Ianno and Hyanno.

…

On June 4, 1639 (June 14, N. S.), the colony court granted permission to Messrs. Hull, Dimock and others “to erect a plantation or. town at or about a place called by the Indians Mattacheese;” …

This Iyanough who issued land was possibly John Hyanno, son of Sachem Iyanough who died in the swamps in 1623 or his grandfather since the colony did not establish Barnstable until 1639. John Hyanno was born around 1621 (as would his sister Mary). Their father died very young in 1623 (mid to late twenties), so his children were very young when he died. In 1639 John Hyanno would have been around 18 or 21 years old – probably not quite old enough to be the Sachem and issuing land grants. But it is possible he was.

Continuing on:

The settlement thus begun in the Mattacheese territory was confined to the northern portion of the present town until 1644, when on the 26th of August, a further purchase of lands of the Indians was made by the town … It was purchased of Serunk, a South Sea chief …

The second purchase , in 1647, was of Nepoyetm, Indian, by Thomas Dimock and Isaac Robinson, who were appointed by the town to act for them. …

The next purchase was in 1648, of Paupmunnuck, a South Sea Indian. …

In 1664 a purchase of the lands of Iyanough was perfected, which gave the town more substantially its present area. … This deed embraced the southeastern part of the present town, except a tract owned by John Yanno, son of Ianogh, in and around Centerville, which was purchased of him in 1680 by Thomas Hinckley in [sic] behalf of the town.

It is worth noting the Iyanough/Hyanno Indian family/tribe retained control of their lands for a long time – well after the period when the Bearse family claims Mary Hyanno married the Barnstable settler Austin Bearse. Basically the Iyanough/Hyanoo family have charter to their tribal lands until 1680.

What one has to wonder is – if Austin Bearse was the son-in-law to Sachem John Hyanno, owner of so much land – why did Bearse not receive some land independently of the English settlement? If his wife was “Princess Little Dove” it would make sense she would receive some land. But Bearse does not move to any Indian land until it was purchased by the local English government.

Something that does not happen in the case of William Cornwell.

As historians note, the remnants of the Indians on the Cape end up migrating to the reservation on Mashpee unless they held tracts of land – which only the Sachem and his family would be able to pull off.

The Wampanoag

One of the strongest Indian Tribes/Nations was The Wampanoag. The Nauset (and therefore the Cummiquid) ended up under the Wampanoag federation after disease decimated the Cape Cod Indians. The Wampanoag play a key role in the decade of interest:

In 1600 the Wampanoag probably were as many as 12,000 with 40 villages divided roughly between 8,000 on the mainland and another 4,000 on the off-shore islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket. The three epidemics which swept across New England and the Canadian Maritimes between 1614 and 1620 were especially devastating to the Wampanoag and neighboring Massachuset with mortality in many mainland villages (i.e. Patuxet) reaching 100%.

…

After anchoring off Cape Cod on November 11, 1620, a small party was sent ashore to explore. Pilgrims in every sense of the word, they promptly stumbled into a Nauset graveyard where they found baskets of corn which had been left as gifts for the deceased. The gathering of this unexpected bounty was interrupted by the angry Nauset warriors, and the hapless Pilgrims beat a hasty retreat back to their boat with little to show for their efforts. Shaken but undaunted by their welcome to the New World, the Pilgrims continued across Cape Cod Bay and decided to settle, of all places, at the site of the now-deserted Wampanoag village of Patuxet. There they sat for the next few months in crude shelters – cold, sick and slowly starving to death. Half did not survive that terrible first winter. The Wampanoag were aware of the English but chose to avoid contact them for the time being.

In keeping with the strange sequence of unlikely events, Samoset, a Pemaquid (Abenaki) sachem from Maine hunting in Massachusetts, came across the growing disaster at Plymouth. Having acquired some English from contact with English fishermen and the short-lived colony at the mouth of the Kennebec River in 1607, he walked into Plymouth in March and startled the Pilgrims with “Hello Englishmen.” Samoset stayed the night surveying the situation and left the next morning. He soon returned with Squanto.

…

Although Samoset appears to have been more important in establishing the initial relations, Squanto also served as an intermediary between the Pilgrims and Massasoit, the Grand sachem of the Wampanoag (actual name Woosamaquin or “Yellow Feather”). For the Wampanoag, the ten years previous to the arrival of the Pilgrims had been the worst of times beyond all imagination. Micmac war parties had swept down from the north after they had defeated the Penobscot during the Tarrateen War (1607-15), while at the same time the Pequot had invaded southern New England from the northwest and occupied eastern Connecticut. By far the worst event had been the three epidemics which killed 75% of the Wampanoag. In the aftermath of this disaster, the Narragansett, who had suffered relatively little because of their isolated villages on the islands of Narragansett Bay, had emerged as the most powerful tribe in the area and forced the weakened Wampanoag to pay them tribute.

It is important to note here the evolving hierarchy of Indian society. Disease forced the independent tribes along the coast to band together to defend against the stronger inland tribes. It is also important to note that Mary Hyanno was allegedly related to Canonicus – Great Sachem of the Narragansett Indians. More on these alleged family connections when we attempt to connect the dots between Mary Hyanno and Williams Cornwell.

It makes sense that to seal a tribal alliance a marriage of lead families would be in order. Therefore having an Iyanough Sachem marry into the Canonicus family – pretty much bridging the Nauset, Wampanoag and Narragansett Indians – is not far fetched. If true, this makes the Iyanough family very, very powerful.

To continue:

Massasoit [Editor: Great Sachem of the Wampanoag], therefore, had good reason to hope the English could benefit his people and help them end Narragansett domination. In March (1621) Massasoit, accompanied by Samoset, visited Plymouth and signed a treaty of friendship with the English giving them permission of occupy the approximately 12,000 acres of what was to become the Plymouth plantation. However, it is very doubtful Massasoit fully understood the distinction between the European concept of owning land versus the native idea of sharing it. For the moment, this was unimportant since so many of his people had died during the epidemics that New England was half-deserted. Besides, it must have been difficult for the Wampanoag to imagine how any people so inept could ever be a danger to them. The friendship and cooperation continued, and the Pilgrims were grateful enough that fall to invite Massasoit to celebrate their first harvest with them (The First Thanksgiving). Massasoit and 90 of his men brought five deer, and the feasting lasted for three days.

To the Narragansett all of this friendship between the Wampanoag and English had the appearance of a military alliance directed against them, and in 1621 they sent a challenge of arrows wrapped in a snakeskin to Plymouth. Although they could barely feed themselves and were too few for any war, the English replaced the arrows with gunpowder and returned it. While the Narragansett pondered the meaning of this strange response, they were attacked by the Pequot, and Plymouth narrowly avoided another disaster. The war with the Pequot no sooner ended than the Narragansett were fighting the Mohawk. By the time this ended, Plymouth was firmly established. Meanwhile, the relationship between the Wampanoag and English grew stronger.

It becomes more and more clear that the English Pilgrims (and later Puritans) had landed into a regional power upheaval among the major Indian tribes. Each Sachem was jockeying for position to rule the others. Each Sachem concluded the English would bring strength (through arms and trade) to vanquish their Indian enemies. And the English would also learn quickly they could play the Indians off against each other. The regional power structure was destabilized by the disease the Europeans brought and everyone was looking to take advantage.

The resultant political tides on both sides would destroy the Indians and frame the manner in which New England evolved.

After 1630 the original 102 English colonists who founded Plymouth (less than half were actually Pilgrims) were absorbed by the massive migration of the Puritans of the Massachusetts Bay Colony near Boston. Barely tolerant of other Christians, the militant Puritans were soldiers and merchants whose basic attitude towards Native Americans was not one of friendship and cooperation. Under this new leadership, the English expanded west into the Connecticut River Valley and during 1637 destroyed the powerful Pequot confederacy which opposed them. Afterwards they entered into an alliance with the Mohegan upsetting the balance of power. By 1643 the Mohegan had defeated the Narragansett in a war, and with the full support of Massachusetts, emerged as the dominant tribe in southern New England. With the French in Canada focused to the west on the fur trade from the Great Lakes, only the alliance of the Dutch and Mohawk in New York stood in their way.

…

Even Massasoit fell in with the adoption of English customs and before his death in 1661, petitioned the General Court at Plymouth to give English names to his two sons. The eldest Wamsutta was renamed Alexander, and his younger brother Metacomet became Philip. Married to Queen Weetamoo of Pocasset, Alexander became grand sachem of the Wampanoag upon the death of his father. The English were not pleased with his independent attitude, and invited him to Plymouth for “talks.” After eating a meal in Duxbury, Alexander became violently ill and died. The Wampanoag were told he died of a fever, but the records from the Plymouth Council at the time make note of an expense for poison “to rid ourselves of a pest.” The following year Metacomet (Wewesawanit) succeeded his murdered brother as grand sachem of the Wampanoag eventually becoming known to the English as King Philip.

…

In late June a Wampanoag was killed near the English settlement at Swansea, and the King Philip’s War (1675-76) began. The Wampanoag attacked Swansea and ambushed an English relief column. Other raids struck near Taunton, Tiverton, and Dartmouth. Despite being forewarned and their advantage in numbers, the English were in serious trouble. Well-armed with firearms (some French, but many acquired through trade with the English themselves), the Wampanoag and their allies even had their own forges and gunsmiths. Drawing from virtually every tribe in New England, Philip commanded more than 1,000 warriors, and even the tribes who chose to remain neutral were often willing to provide food and shelter. Only the Mohegan under Oneko (Uncas’ son) remained loyal to the English. Particularly disturbing to the colonists was the defection of most of the “Praying Indians.” When Puritan missionaries attempted to gather their converts, only 500 could be found. The others had either taken to the woods or joined Philip. Their loyalty still suspect, the Praying Indians who remained were sent to the islands of Boston Harbor and other “plantations of confinement.”

It is truly sad and tragic that the tribe that came to the rescue of Plymouth and feasted at the first Thanksgiving had been over time so abused it rose up in war and was annihilated. The fate of Massasoit is even more tragic, as the English rulers gave him up to his arch enemy Uncas of the Mohegans to be killed (see here for the story). It is in this swirl we find William Cornell and his wife Mary.

The Narragansett

If we count the Wampanoag as the first large Indian Nation we need to address, the second would be the Narragansett. As I noted in the second post in this series, this tribe had a special relationship with the English. The English colonies bifurcated into the Puritan zealots who felt empowered by God to destroy the heathen and those who felt it was God’s intention for them to respect the natives. The Narragansett were unique in their relationship with the English settlers, in that they eventually treated with the zealots, but provided sanctuary to those who felt “differently”:

The pre-contact wave of epidemics which swept across New England and the Canadian Maritimes between 1614 and 1620 somehow missed the Narragansett …probably because of the isolation of their villages on the islands of Narragansett Bay. With their population relatively unscathed and later reinforced by incorporation of survivors from other tribes, they emerged from this disaster as the dominant tribe in southern New England and subjugated many of their neighbors. …

In 1622 the Pequot attacked the Narragansett who seized a disputed hunting territory in southwest Rhode Island from them. The following year the Narragansett were drawn into in a prolonged war with the Mohawk during which Pessacus, an important sachem, was killed. By the time the Narragansett were free to deal with the English at Plymouth, they were firmly established, and large numbers of Puritans were settling at Massachusetts Bay.

In the beginning, the English were content to leave the Narragansett alone. In 1627 Plymouth made an agreement with the Dutch not to trade in Narragansett Bay. Canonicus [editor: grand Sachem of the Narragansett] remained aloof from the English colonists, but he could not ignore the defection of the Wampanoag. In 1632 he decided to reassert his authority over them, but when the English colonists supported the Wampanoag, the Narragansett were forced to abandon the effort. The English had altered the balance of power in the region but would soon make themselves felt in other ways. …

Rogers Williams was a man of uncommon integrity who believed the English king had no right to claim to native lands, and because he did not hesitate to express this in public, the Puritans banished him from Massachusetts as a dangerous radical. Forced to move to Rhode Island in 1636, his negotiations to purchase land from the Narragansett initiated a long period of mutual trust and respect which continued until the King Philip’s War (1675-76). Williams’ accommodation with the Narragansett was timely, since the beginning of English settlement in Connecticut had provoked a serious confrontation with the Pequot. …

The Narragansett play a key role in the coming Pequot War (1636-1638) and in the power struggle that ensues after the war. But what is of interest to our topic is not just the Naragansett relationship to the Wampanoag and Nauset, but their alliance to the Indians of the Connecticut River made prior to the war with the Pequots.

The Wangunks

The so called “River Indians” ranged the length of the Connecticut River Valley – a region of wondrous farm land, abundant wild game and excellent river access. It was the envy of the English, the Dutch and the Pequot. The Indians here were called many names, but are most known as the Wangunks:

In subsequent years, Wangunk territory became a focal point for the developing European fur trade, as the tribe’s position along the river provided a ready access to more inland forests, where the fur-bearing animals thrived. For that reason, the Wangunk fell victim to Pequot expansion at the start of the seventeenth century, as that tribe attempted a measure of control over trade-related resources.

After losing three battle contests, the Wangunk became tributaries to the more powerful Pequot. Frustrated by this situation, their sachem Sowheage created alliances with the equally powerful Narragansett by the marriage of one of his family to Massecump, the son of the Narragansett leader Miantonomo. Looking for broader allies, one of Sowheage’s sons travelled with a diplomatic envoy from the River tribes in 1631 to Massachusetts, where a community of English separatists had recently arrived, in hopes of persuading the newcomers to settle along the Connecticut River.

Here I wish to note th tribal alliance sealed by a marriage into the family of Canonicus (the uncle of Miantonomo, grand-uncle of Massecump). Massecump could claim his grand uncle to be Canonicus and his father-in-law to be Sowheag – two very powerful Sachems. These marriage bonds between tribes included defensive alliances against enemies. So the Wangunk and Narragansett had an alliance stronger than one of tribute.

More importantly to our ‘story’, Sowheage and the Wangunks later become hosts/neighbors of William Cornwell after the Pequot War. And it is the Wangunks who sell the land that would become Hartford to the English settlers that led the battle against the Pequots. The Wangunks play a much bigger role in events than history tells.

Another interesting event is when Sowheage moves his tribal”capitol” to a place near and dear to William Cornwell and his extended family:

The first to establish a permanent European presence, however, were the Dutch. In 1633, the West India Company purchased land at Suckiog from the local Native proprietors to build a fortified trading post called the House of Good Hope. This was followed in quick succession by English settlements at Matianuck (Windsor) in 1633, Pyquag (Wethersfield) in 1634, and Suckigog (Hartford) in 1636.

It is suspected that Wethersfield’s displacement of Sowheage to Mattabesett in disregard of its treaty responsibilities led the sachem to reconsider an alliance with the Pequot. … The Wangunk and their Narragansett allies spent more than a decade fighting with the Mohegan over control of territory and political power.

At the same time, however, affairs between the English and the Wangunk had improved considerably. Sowheage allowed Connecticut Governor John Haynes to expand further into Wangunk country and eventually conveyed to colonial authorities a large tract of land. After Sowheage’s death in 1649, the General Court established the English settlement at Mattabesett (later renamed Middletown) and reserved two parcels of land for Sowheage’s descendants: one fifty-acre tract at Mattabesett and three hundred undefined acres at Wangunk.

This is a very important set of facts related to our topic. Sowheag transfers the land on the Connecticut River to the English to settle West of the Pequots, while he has a marriage bond with the Narragansett tribe who live East of the Pequots. Then he moves his center of power to Mattabesett (or Mattabeseck, Mattabesick).

In the next post we will explore the Pequot War and how it provided various possible nexus points for William Cornwell to become an undocumented ally of the Wangunks and Naragansett. There seems to be a hint of an alliance of Indians and Settlers that opposed both the zealots of the Puritan colonists and the political machinations of Uncas – Sachem of the Mohegan Indians who were once Pequot warriors.

It is well documented William Cornwell settles in Middletown as a founder, and raises his family. It is also well documented Cornwell co-existed with Sowheage and owned land adjoining or within Sowheage’s famous Indian Hill:

Sowheig, or Soheag, was the Great Sachem, or Sassanac, of this powerful tribe of Mattabeeseecs. Before the settlement of this town he sold to Mr. Haynes, governor of Connecticut, a great part of the township. Sowheig ruled over a large tract of country on both sides of the Connecticut River, including the Piquag or Wethersfield Indians, also a tribe on the north branch of Sebethe River in Berlin. The township of Farmington is supposed to have been part of his dominions.

He lived on Indian Hill. When he wished to assemble his braves for council or war, he would stand on the hill, and blow a powerful blast on his wondrous horn or shell, which could be heard all over the surrounding country, and the fleet-footed warriors would soon come rushing in from east, west, north and south, in answer to the call of their mighty chief. This shell, or horn, was far famed among the neighboring tribes and white settlers for its wondrous, far-reaching sound.

William and Mary Cornwell’s first son (Sgt John Cornwell) is not only listed as being born in 1640, he is listed as being born in Middletown! Not Hartford. I will be double checking, but I am sure all but 2 of their children were born in Middletown, before 1650 – when the town was established. So it seems clear Cornell was in Mattabesett earlier than current historical documents have considered.

As was noted in a previous post in this series, the establishment of the English town of Mattabesett in 1650 does not mean that is the date of first English settlers. It is simply when the Connecticut government recognized the town as an English entity.

The Pequot/Mohegan

The final large tribal group that plays a key role in this decade of interest is the Pequot and their splinter group the Mohegan:

At the time of their first contact with Europeans, southeastern Connecticut from the Nehantic River eastward to the border of Rhode Island. Both the Pequot and the Mohegan were originally a single tribe which migrated to eastern Connecticut from the upper Hudson River Valley in New York, probably the vicinity of Lake Champlain, sometime around 1500.

…

But rather than uniting to destroy the new English trading post on the Connecticut, the Pequot split into pro-Dutch and pro-English factions.

The division had its roots in the personal rivalry between Sassacus and his son-in-law Uncas. Both had been sub-sachems and expected to succeed the grand sachem Wopigwooit when he died in 1631. However, the Pequot council selected Sassacus, and Uncas never accepted this. Their rivalry continued afterwards in bitter council debates over the fur trade. With Sassacus favoring the Dutch, a pro-English faction gathered around Uncas. The arguments grew increasingly heated which made trade along the Connecticut River dangerous for both Dutch and English with the different Pequot factions killing and robbing traders unfortunate enough to cross paths with the wrong group of them. Uncas was eventually forced to leave and form his own village. Other Pequot and Mattabesic soon joined him, and taking their name of Uncas’ wolf clan, the Mohegan became a separate tribe hostile to the Pequot.

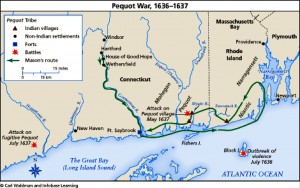

The civil war between Uncas and his father-in-law Sassacus culminated in the Pequot War, with Uncas and the Mohegans allied with the English to massacre the Pequots at their compound called Mistic. It is this massacre that brings Cornwell, under Captain Underhill, from Roxbury, MA into Connecticut.

As seen in the following map, Uncas and the Mohegans were not just pro-English, they were also situated near the fledgling English colonies of Windsor, Hartford, Westerfield and Saybrook along the Connecticut River. Sassacus and the main Pequot enclaves, while pro-Dutch, were located closer to the Bay Colony and Plymouth; their border with the Naragansett in Rhode Island.

The Pequot War not only dominates the decade 1630-1640, it is a major factor in how William Cornwell came to Mattabesett/Middletown. Cornwell fights in the war alongside key players, including the Naragansett Sachem Miatonomo and the Wangunk Sachem Sequesson.

Cornwell seems to be more allied with the separatists than the Puritan Zealots, a position likely reinforced by the massacre of the Pequot – an event seemingly orchestrated from the settlement of Hartford with the support of Uncas.

In the fourth installment I will begin to connect the data and explore the likely Indian connection with William Cornwell. And then we will look at the rumor of Mary “Little Dove” Hyanno.

Pingback: Tracing Our Family To The 1600’s In New England, Part 4 | Our Family History

Pingback: Tracing Our Family To The 1600’s In New England, Part 1 | Our Family History